By Robyn Murray

Before the movers came to pack everything up, Carol Moseman stepped into one of her favorite rooms and took pictures. Filling the walls were more than 60 works of art that had resided in her home for years. Sculptures and drawings, bold oil paintings and colorful pastels — all special, all painstakingly chosen and collected with her husband, Mark, over the last 50 years.

As she walked past, Carol recalled the days they purchased each one.

“There are paintings I’m going to dearly miss,” she said, “but I know that they’re going to be safe.”

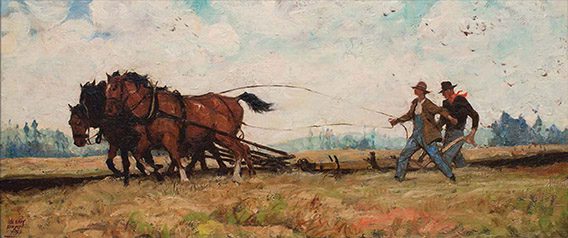

The Moseman collection totals more than 200 works of art, an eclectic array of styles and renowned artists from America and Europe, with one thread that weaves them together: humankind’s relationship to the land. Today considered a collection of significant artistic and historic value, the works fall under the genre of agrarian art — a term that was coined by Mark, a well-respected agrarian artist himself, and is now recognized by the Smithsonian Institution.

Over the years, Mark and Carol have donated pieces from their collection to several museums and are now giving the remainder to the Great Plains Art Museum, which is housed at the Center for Great Plains Studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. They have also set up a generous bequest to endow the collection and ensure it forever remains preserved and accessible.

“It feels good, because it will have a home,” Carol said. “People will be able to see it long after we’re gone. People will be able to see the stories in the paintings.”

Those stories are what is most meaningful to the Mosemans, partly because their lives are reflected in them. They grew up in small-town Nebraska — Mark outside Oakland and Carol in Brainard — descendant from immigrant homesteaders and settlers who came to Nebraska in the 1800s and set up modest family farms.

It was a family tradition bigger than their experience. It was fundamentally tied to the early vision of America — its identity, culture and values. As Thomas Jefferson imagined, family farmers would form the foundation of democracy as embodiments of the spirit of hard work and independence.

“As close to the Jeffersonian ideal in America, we lived it,” Mark said. “We took it for granted. We didn’t know there was anything else. We didn’t know it would ever change.”

Mark said his earliest memory on the farm was putting up hay with his father and grandfather. He recalls a vibrant family and social life on the farm and in the surrounding community — the farms were small, and the families helped each other.

But as they grew older, Mark and Carol saw that centuries-old farm life begin to change. Hands-on labor transitioned to mechanized farming, which required fewer and fewer people. As technology advanced, farms got bigger and the small towns that depended on their business emptied out. In fact, 23 million Americans lived on farms in 1953, according to the Population Reference Bureau. Today, just 3 million do.

It has been a significant exodus — one of the largest movements of Americans in the country’s history. But it happened slowly.

“It was a gradual, slow death,” Mark said. “Farmers have lost their family farms and gone to work at McDonald’s or whatever, and a number of them committed suicide, feeling they were failures, when it was really the economy had changed.

“The loss of those people and culture is something that should be noted. It shouldn’t just be something that dies on the vine.”

The Mosemans decided to do their part to document that story — not just the exodus from the farm, but the way our relationship to the land has changed and what has been lost in the transformation, including our role and responsibility as caretakers.

Today the Moseman collection is one of the few art collections — if not the only one — to tell the story.

“This art has more than a simply feel-good purpose,” Mark said. “It has a purpose where hopefully it can have an impact on people who see it.”

The Mosemans selected the Great Plains Art Museum as the beneficiary of their collection because they believe it is uniquely suited to house it. Beginning July 2, selections from the Moseman collection will be on display at the museum. “Agrarian Spirit in the Homestead Era — Artwork from the Moseman Collection of Agrarian Art” runs through Oct. 23, and full-color catalogues of the exhibit are on sale to benefit the museum.

The connection is also personal. As an artist, Mark was offered a one-man exhibition by the Great Plains Art Museum in 2004. He said that meant a great deal to him, and he feels the collection has found a perfect home.

“It will feel really good that they’re organized in a really thoughtful fashion … that it’s museum-worthy,” Mark said, “We will feel we’ve accomplished something in life that no one else really could do but for a vision that we had.”

“It will feel really good that they’re organized in a really thoughtful fashion ... that it’s museum-worthy.”

Mark Moseman

You may also like ...

Investing in the Future: Strengthening UNK’s College of Education

.”…The fund is critical in not only community building but also articulating what is going on in the UNK campus to the rest of the world, and especially to our state.”

Shaping Tomorrow’s Sound: The Impact of Jazz at UNO

“When I see former students out in the world making music, it reminds me why I do this. This program changes lives.”

Investing in the next generation through the World Class Actuarial Science Fund

“Every donation honors UNL’s actuarial legacy and invests in the next generation. It’s more than just a program; it’s a community that continues to grow and thrive.”