UNMC graduate overcomes obstacles to embrace opportunities.

His mom made him look at her hands.

They were swollen, again.

She reminded him how much they ached, day after day, from her job packaging meat at a factory in Columbus, Nebraska.

“She told me, ‘This is the reason you have to go to college. You should get an education. It’s going to help you in the future,’” Radiel Cardentey-Uranga, a recent graduate of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, says.

A few weeks before his graduation, Cardentey-Uranga turned 23. He dreams of a career in radiography, using his hands to help people. He sees that career within his reach now — and maybe, down the road, he’ll become an M.D. or Ph.D. or a physician’s assistant — and he sees himself giving back to the community one day. He knows it’s all thanks to his parents and teachers and all the people who extended their hands to him along the way, pulled him up to where he is today.

To who he is today:

A hardworking, recent college graduate, the first in his family to attend college …

A grateful recipient of two UNMC scholarships: the Charles R. O’Malley Scholarship and the Hermene K. Ferris Scholarship, generous gifts from people who don’t even know him …

A proud citizen of the United States, as of last summer …

And a proud narrator of a very unlikely story. One he can hardly believe himself, he says, as he tells it over the phone from his home in Columbus, Nebraska.

His story began in Cuba. It began even before he was born, when his hardworking dad was thrown in jail for two years for speaking out against the government.

“He just wasn’t in favor of the tyranny or the dictatorship they had,” Cardentey-Uranga says. “He was publicly speaking the truth that the government doesn’t want you to tell.”

When his dad got out of jail, he tried to go back to working in construction. He had a good reputation working with his hands, in masonry. But police were always giving him citations, harassing him, ticketing him. Cardentey-Uranga’s family eventually applied to come to the United States as refugees and was accepted.

Cardentey-Uranga was 16 when he came over with his parents and older brother. After some time in Washington state, his parents split up. Cardentey-Uranga and his mom came to Columbus, where his mom, who had used her hands doing hair and nails out of her home back in Cuba, took on that tough factory job.

Cardentey-Uranga could barely speak or understand English, so he wasn’t much of a student at first at Columbus High School. He’d dropped out of school in Cuba in ninth grade because of his family’s fears that if he kept going, he’d get taken away and thrown into military service, which in Cuba is mandatory.

He struggled because of those years of school he missed, especially in math and physics.

“Basically,” he says, “I had to learn it all from scratch.”

He joined the high school soccer team, which helped because some of the players spoke Spanish. He took a weekend job at an animal shelter, and that helped him learn English. He started to fit in.

A few teachers took him under their wings, encouraged him to try for higher education and pointed him in the direction of Central Community College.

But he didn’t think he was college material. He figured he’d just find a factory job, too, when he graduated.

That’s when his mom made him look at her swollen hands.

“She said, ‘This is the reason you have to go through school. I’m making the sacrifice for you. You should take a chance at the opportunity,’” Cardentey-Uranga says.

He did. He started asking questions about the path to higher education. He took the ACT but scored poorly at first. He started at the community college, way behind the other students. He took evening classes, summer classes. He got to know one of the Spanish instructors there, and she suggested he consider a career in radiography. She told him UNMC had a radiography program he could take right there in Columbus.

Radiography?

He researched it, loved what he saw and applied to the program at UNMC, which has a partnership with a hospital in Columbus. As part of the application process, he was required to do a three-day job-shadowing stint to make sure he really wanted to work in that field.

“I liked the job,” Cardentey-Uranga says. “I felt like it really fit me because I’m using my hands constantly, in different ways. You use the computer sometimes; you’re constantly running around and moving. I like to move. And you get to work with people from all different backgrounds and cultures.”

He applied for scholarships. Then he forgot he’d done so, until one day when he opened an email telling him he’d received the O’Malley and Ferris scholarships. The O’Malley Scholarship was created by the largest gift to benefit UNMC’s College of Allied Health Professions students to date. Besides allowing the college to endow funds for a cohort of “O’Malley Scholars,” the gift provides an additional $500,000 if matched by other allied health donors through 2022. The matching arrangement allows benefactors to endow their own named scholarships, with the benefit of doubling their gift.

“When I got it,” he says. “I got an email telling me and when I read it, I was like, OK, this can’t be real. They probably sent it to the wrong person!”

He laughs.

“But I guess someone realized that I was really working hard to achieve good academic performance. And I got the scholarships, and they truly make a difference. The money helps out with school. But what also really impacts me is the fact that it makes me know there are people out there who are actually invested in your future, who really care about you.

“That’s what impacted me the most — that there are people looking out for me, people who care.”

Cardentey-Uranga graduated from UNMC with a bachelor’s degree in medical imaging and therapeutic science this past May. He will go on to receive a post-baccalaureate certificate in cardiovascular interventional technology through UNMC.

He wrote a thank you letter last May to the people behind the Ferris Scholarship:

I am looking forward to achieving my career goal at UNMC and hopefully someday to be in your shoes and give back to the community in the same way you are doing with me.

He also created a video for the trustees of the O’Malley Trust, telling them his unlikely story and thanking them for their big hand in it.

And promising his story will continue.

"She told me, 'This is the reason you have to go to college. You should get an education. It’s going to help you in the future.'"

Radiel Cardentey-Uranga

You may also like ...

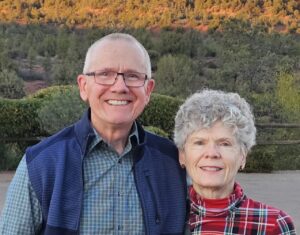

After Years of Service, Donors Leave a Legacy

Claudia and John Reinhardt, DDS, are Burnett Society members who have established a planned gift to support the UNMC College of Dentistry in Lincoln. John is dean emeritus and a professor in the Department of Adult Restorative Dentistry at UNMC, and Claudia has had a long career in nonprofit and higher education communications.

Moving the Needle on Diabetes

A visionary gift is transforming diabetes care in Nebraska and beyond.

The Future of Health Care Is Being Built in Nebraska

Project Health is more than a building. It’s a $2.19 billion vision to transform patient care, train the next generation of health care professionals, fuel research and boost Nebraska’s economy.