UNK’s STEM Building Encourages Collaboration and Discovery

By Kristin Howard

“Do you know what a flip phone is?”

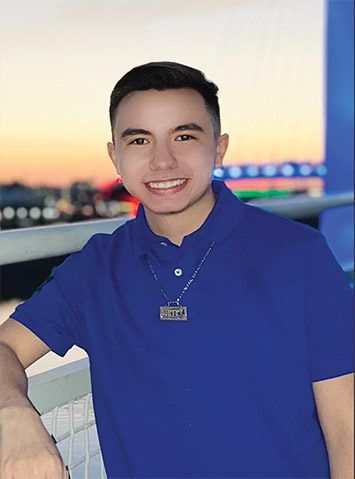

University of Nebraska at Kearney student Uriel Anchondo loves discovery and being connected.

For him, the flip phone is more than just an artifact of his childhood; it’s a symbol of his academic and career goals.

“I was 8 or 9 years old, always on my mom’s flip phone, changing the settings, finding interesting information, showing her that I could change the language to Spanish,” said the first-generation college student from Grand Island, Nebraska. “I loved figuring it all out.”

This curiosity — along with a supportive family, scholarships and motivation to succeed academically — has propelled Anchondo on what he calls “an incredible path.”

An applied computer science major with a minor in finance, Anchondo spends much of his time in UNK’s Discovery Hall. The state-of-the-art STEM facility is home to the construction management, industrial distribution, interior and product design, aviation, cyber systems, mathematics and statistics, physics, astronomy and engineering programs. The hall opened in August 2020, replacing the Otto C. Olsen industrial arts building.

Located on UNK’s west campus, Discovery Hall was designed specifically for the programs that will drive economic growth in greater Nebraska.

“The name Discovery Hall is so appropriate,” said UNK Chancellor Doug Kristensen at the facility’s ribbon-cutting ceremony in 2020. “This building is not a lecture hall. This building is all about discovering new things and having people work together. Truly, there will be lots discovered in this building, and it’s going to benefit our students and our state.”

This first-class facility, he said, will change Nebraska by offering opportunities for current and future students that “we’ve never dreamed of before.”

For Tim Jares, Ph.D., dean of the UNK College of Business and Technology, Discovery Hall is a special place.

“Students and visitors are engaged in the learning environment from the minute they walk in the door,” he said. “The lab spaces are specially designed to facilitate experiential learning. Learning by doing means our students will retain much more of what they learn and will be much better equipped to make informed career decisions.”

Anchondo’s goal is to work for a big tech company, and he said he had a vision of his future when he entered Discovery Hall for the first time.

“There was glass everywhere, sleek furniture and workspaces … and we get to learn there!” he said.

Discovery Hall’s open floor plan was intended to promote collaboration and innovation across different academic departments. Anchondo discovered this collegiality extends throughout the university.

“My favorite part about UNK is that I have discovered other communities and groups on campus that have allowed me to branch out and connect,” he said.

After graduating from UNK, Anchondo would like to work as a computer or business systems analyst.

“UNK is helping me achieve this goal by providing resources and networking opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t be possible,” he said. “My family is so grateful; I am so grateful. I want to travel the world and explore everything.”

And his analogy takes it full circle: “Before, it was just a flip phone. Now we’re all connected.”

“This building is not a lecture hall. This building is all about discovering new things and having people work together. Truly, there will be lots discovered in this building, and it’s going to benefit our students and our state.”

Doug Kristensen, UNK Chancellor