By Robyn Murray

The first days on a college campus can be intimidating. For freshman students, the web of buildings can seem impossible to navigate. Their professors can seem daunting, their peers unwelcoming. And if those new students find no one who looks or sounds like them, intimidating can turn to overwhelming.

That matters.

It means when something happens to push them off track — a messed-up assignment or flunked test, a harsh assessment from a professor or tardy write-up, they might ask themselves: Do I belong here? Can I succeed? Or should I quit and go home where I can be myself?

That’s what it felt like for Fernando Wisniewski-Pena.

A first-generation American, Wisniewski-Pena is also a first-generation college student. His parents grew up in Mexico and knew little about how to prepare him for college life in Lincoln, Nebraska.

“I really didn’t know the expectations of asking for help,” he said. “Not knowing exactly who to talk to or how often to talk … I didn’t know if I was being too overbearing or if I was being too needy.”

Wisniewski-Pena struggled with his classes and was put on academic probation in his first year. That’s when he really began to wonder if he was in the right place.

“I think everybody has had that epiphany moment of, like, do I belong here?” he said. “I know how it feels personally to question my existence here at the university.”

Students who feel like they don’t belong on campus have a much higher chance of dropping out. According to a 2017 report by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Black and Hispanic students graduate at rates significantly lower than white and Asian students.

But the University of Nebraska–Lincoln has a strong record of closing that gap. In 2015, a report by The Education Trust ranked UNL first among the nation’s public colleges and universities in improving graduation rates for underrepresented students.

Some of that credit belongs to a 30,000-square-foot building — complete with large windows and sweeping views of campus, comfortable reading spaces and a welcome-all atmosphere: the Jackie Gaughan Multicultural Center.

Ten years ago, the Gaughan, as it’s known, was built to provide a welcoming place for students who don’t fit the default demographic on campus. It was named in honor of Jackie Gaughan, a colorful casino magnate who believed things work better — businesses, communities and society at large — when everyone has a voice at the table.

As the Gaughan celebrates its 10-year anniversary, students and faculty are reflecting on what has changed in the decade since its opening — and what has not. For many, the challenges faced by minority and underrepresented students feel like they’re stuck on repeat. And 2020 returned them all to the fore.

While the work is far from done, at the Gaughan, students feel like it’s possible. They feel at home — welcomed, seen, respected and championed. They feel hopeful that real change will come.

As it stands, attached to the beating heart of campus, the Nebraska Union, the Gaughan is one of the largest multicultural centers on a U.S. university campus. With spaces like the Kawasaki Reading Room, where students can learn about Japanese history and art, as well as massage chairs and reading nooks, the Gaughan is a place for students to study, unwind and gather.

It is also home to more than a dozen student organizations, such as the UNL Disability Club, Afrikan People’s Union and the Muslim Student Association.

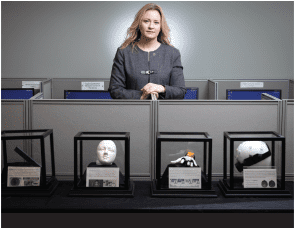

“We have wonderful spaces where we can offer tutoring and assistance academically, so students can find their way and be successful,” said the center’s director, Charlie Foster. Foster is also the assistant vice chancellor for inclusive student excellence and director of the Office of Academic Success and Intercultural Services.

“We work hard to make them feel comfortable, make them feel like they belong on campus, that they can be successful here,” Foster said.

When Wisniewski-Pena was struggling with his classes, he was connected to an adviser at the Gaughan, and the relationship he developed made all the difference.

“If it wasn’t for her, I probably wouldn’t have graduated,” he said, calling the Gaughan his “home away from home.”

“Just knowing that these individuals knew where I was coming from,” he said, “I had more than just an academic connection; I had a personal connection.”

Unyoh Mbilain had a similar experience. A first-generation American, Mbilain is a political science and global studies major on a pre-law track. Her parents immigrated from Cameroon, and she says the Gaughan staff have become like family.

“Miss Charlie … she’s like our mom away from home,” Mbilain said. “She’s always checking up on us.”

Mbilain attended a competitive private school and her parents went to college, so she didn’t feel lost on campus. But she did feel alone at times as one of the few Black faces in class.

“I know I wouldn’t have been at UNL for that long if … I didn’t have the Gaughan to blow off steam,” she said. “It’s important to have a place that represents you … it’s definitely part of my well-being.”

Foster says the Gaughan welcomes students from every walk of life — big cities, small towns, Nebraska natives or foreign — and understands diversity encompasses much more than skin tone.

“Suggesting that multiculturalism is only about black and brown faces, that’s an error,” she said. “We’re supposed to be learning about everybody and learning what richness we all bring to the table.”

Inclusive Student Excellence

In 2020, UNL released a strategic plan that laid out a 25-year objective. The goals include enhancing research and creative activity, preparing students to be lifelong learners and broadening Nebraska’s engagement in community, industry and global partnerships. For every goal, one principle is woven in: Create an institution where “every person and every interaction matters.”

It’s a worthy concept, but it also points to an uncomfortable truth.

“The fact that we have to explicitly say that means that maybe up to this point not everybody has felt that they mattered or that they belonged,” said Tyre McDowell Jr., assistant vice chancellor for student affairs.

McDowell oversees various student organizations on campus and says his mission is to “create a community where everybody can be their fully authentic self.” Only when students, faculty and staff feel they can truly be themselves do they reach their full potential, he said, and only then does the university get the best from its greatest resource.

McDowell said as the populations served by universities changed, tensions inevitably resulted. How people from diverse backgrounds are perceived or acknowledged on campus or represented within the curriculum needed to be addressed.

“What changes do we need to make, structurally or culturally, to make the college experience at the University of Nebraska one that everybody feels like they’re acknowledged and that they truly matter and belong?” McDowell said. “You can’t wish it away. You can’t write it away. There are things you have to do, and it’s challenging, difficult work.”

McDowell says that work is about confronting a system so that barriers are no longer in place. For example, colleges were not designed for students who are the first in their families to attend university.

“I was a first-generation college student,” McDowell said. “I can tell you, my kids have a distinct advantage having had a parent who’s navigated the college system.”

Colleges were also not designed for students who don’t have money at home. Tuition and textbooks are expensive, and many students work to pay rent while they’re at school. That means they don’t get to participate in research projects or unpaid internships that can make them more attractive to employers when they graduate.

Curriculum and representation are also challenges.

“A student could come to the University of Nebraska, and if they’re a Black student, never having been in the classroom with the person instructing the class looking like them,” McDowell said. “It’s difficult to understand unless you’ve had to navigate that.”

The university’s plan has another stated goal: Create a climate that emphasizes, prioritizes and expands inclusive excellence and diversity. One step forward on that path was welcoming the inaugural vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion to the university, Marco Barker, Ph.D., in 2019. In an email, Barker said the creation of his position symbolized the work of inclusion and diversity as an important campus goal.

“However, the creation of this role acknowledges that diversity as a priority was not understood as a priority by all,” he said. “There is an opportunity and need for our faculty, staff and students to see themselves as part of our inclusive excellence mission and play a role in making diversity, inclusion and equity — including racial equity — a core component of the UNL experience.”

Foster said part of the work is simple: Do a better job of being good to each other.

“That’s what inclusive student excellence is,” she said. “It’s the reason why we do the work that we do. So everybody has a shot at having a great education. And the only way to do that is to do that together.”

Old Lessons, Relearned

While 2020 was one of the most difficult years for many in recent memory, it also moved the nation forward on some critical issues. The killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer brought people of every background to the streets with a unified voice — Black lives matter. No more, but no less. More Americans participated in BLM protests than any other in U.S. history.

As Nebraska students joined in, the Gaughan stood behind them.

“We sought to support all of them,” Foster said. “We were there, because our students were there.”

But while the magnitude of the protests was unprecedented, the conversations and concerns were not new. Foster said 2020 looked a lot like 1968.

“We should be really intentional about learning our history, as a country, as a state,” she said. “If we’re smart now, we won’t have to relive it all over again. We don’t have to keep doing this.”

McDowell said the events of 2020 pushed NU to confront issues like race and racism in a way it has not had to in some time.

“The University of Nebraska doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” he said. “We know that racism exists on the University of Nebraska campus, because we know that racism exists in the society at large. We are a microcosm.”

McDowell said the protests provided an opportunity to have an honest conversation about race and racism in ways that could lead to long-term, systemic changes. But he worries students will get burned out if those changes don’t happen soon.

“Hopefully, the students who are advocating for change don’t grow weary of pushing,” McDowell said. “It can be tiresome … but we need them to keep the pressure on.”

Wisniewski-Pena is one of those students who is pushing for change. He sits on the diversity and inclusion committee in student government and works to ensure students like him feel included. It’s a stop on the path to his goal of practicing international law and working in foreign affairs. It is a destination he is one step closer to as a proud college graduate — thanks to the Gaughan and his own determination.

“I was stubborn,” he said. “Even though there is not a big space for me here, I’m going to make it my space, you know, I’m going to find my community.

“I don’t know where I would be if I had dropped out. I don’t have a backup plan.”

"I really didn’t know the expectations of asking for help. Not knowing exactly who to talk to or how often to talk … I didn’t know if I was being too overbearing or if I was being too needy."

Fernando Wisniewski-Pena