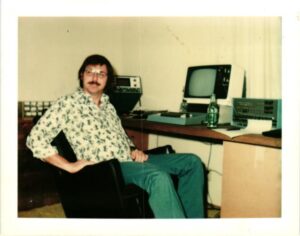

Jerry Varner earned his bachelor’s degree (1963), master’s degree (1965) and doctorate (1972) — all from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln — in electrical engineering.

Jerry became a member of the Burnett Society in 2015 when he decided to include the University of Nebraska Medical Center in his estate plans.

After teaching in the electrical engineering department at UNL for 54 years, he currently serves as the head undergraduate adviser. In addition to his career at UNL, he consulted for the National Institutes of Health for 20 years and enjoys tutoring fifth-grade math students at a local elementary school.

Let’s learn more about Jerry and why he supports NU.

What was the first job you ever had?

My first job was selling popcorn in the lobby of the Rivoli Theatre in Seward, Nebraska. I was in middle school and worked there until I went to UNL. I eventually did everything there except sell tickets. I was even one of the projectionists. That was a time when movies were going to widescreen and the technology was changing. It intrigued me because I have always liked the engineering aspects of how things work.

Best advice anyone ever gave you?

The best advice I can give is “smile and the whole world smiles with you; cry and you cry alone.” It doesn’t do any good to be negative. Being positive helps you learn from adversity, which is always the best learning experience. As a teacher, I try to get students to be problem solvers and productive contributors to society. Technology by itself is not the answer. It’s what can be done with it in beneficial ways that is.

Who is someone from history you’d want to invite to a dinner party if you could? And why?

I would invite Leonardo da Vinci to my place for dinner because he was the original Renaissance man. He was able to be a changing force in both science and the arts. He was centuries ahead of his time in his conceptions of what was possible and had workable theories to achieve those dreams.

What is the first question you’d ask that guest from history?

I would love to ask him what he thought about the world around him and the scientific and art culture at the time he was living.

What is the one song you would be sure to play to set the mood at that dinner party?

I tried to find a song that would encompass engineering to set a mood and found “Make a Circuit With Me” on Google. It’s a real song from the ’70s, but probably not very popular.

What is the question you like being asked the most?

I like being asked how long I’ve been teaching and why. I’ve really been teaching since my grad school days in the ’60s. I never intended to be a teacher, but I had a professor while I was a grad student who had me write one of the labs he was teaching. He then said, “Well, Jerry, you wrote this lab, why don’t you just go ahead teach it?” — which I did. He also had me fill in for him in other classes when he was gone, more and more often. I found I really liked the teaching experience and seemed to connect well with the students.

I think that professor, who was really my mentor, did all that on purpose because he saw the teacher potential in me, and I’m glad he did. As I mentioned before, I enjoy the life skills that I hopefully am able to pass along to students in my teaching — things like problem solving, common sense and value-based decision making. And if a little engineering gets thrown in there, well then, that’s all the better! Ultimately, I try to get my students not to fear failure.

Why do you plan to leave a gift to the University of Nebraska in your estate?

Because of my recent experience with the University of Nebraska Medical Center, I am including them in my estate plans. I want to help make a difference in people’s lives by making available new and better health care for everyone. And on top of that, I get such a great feeling when I’m “giving back.” No chemical drug can make me feel the joy I get when I am able to help somebody by giving back. And I don’t just mean financially. Giving back also means giving time for a cause, not for me, but for others and those who may follow us. I hope that no matter what my physical condition may be, I’ll always be able to do something in the spirit of contributing.

"I want to help make a difference in people's lives by making available new and better health care for everyone. And on top of that, I get such a great feeling when I’m 'giving back'. No chemical drug can make me feel the joy I get when I am able to help somebody by giving back."

Jerry Varner

You may also like ...

The Type of Learning He Can Get Behind: Hands On

Don Chamberlain first fell in love with computer programming at UNL. After a varied career in the computer industry, Don decided to give back to future students at his alma mater.

‘Now It’s My Turn to Give’

Jennifer Jennings, Ph.D., has established a planned gift to support scholarships and experiential learning opportunities for students at the University of Nebraska at Kearney. Read her Q&A.

Fighting Cancer by Giving Back

After several family members fought and succumbed to cancer, Doris Jones decided to give back to future generations by supporting cancer research.